Toxic waters, dying soils: The environmental toll of misused inorganic fertilizers

9 min read

In the quiet village of Nyakaguhu, nestled in Kinini cell, Shyogwe sector of Muhanga district, in the southern province of Rwanda, Mukamwiza Thérèse once lived in harmony with the nature. But today, her home near Rugeramigozi marsh has become a battleground against an invisible threat. Swarms of mosquitoes, multiplying at an unprecedented rate, now invade her community, bringing a surge in malaria cases.

Environmental experts point to an unexpected culprit: the vanishing frog and toad population in Rugeramigozi marsh, a consequence of excessive and poorly managed use of chemical fertilizers. Frogs and toads, nature’s natural pest controllers, are disappearing, leaving mosquitoes to breed unchecked in the stagnant, polluted waters. The story of Mukamwiza and her neighbors is not an isolated one; across Rwanda, the reckless use of chemical inputs is disrupting delicate ecosystems, poisoning water sources, and endangering both human and environmental health.

The silent killers in Rwanda’s ecosystems

Rwanda’s ecosystems are facing a growing threat from the misuse of industrial fertilizers, a silent but devastating problem affecting both the environment and public health. Experts warn that excessive use of these chemicals is contaminating soil and water, leading to far-reaching consequences for aquatic life, human communities and soils.

Speaking to the Rwanda Environmental Journalists, Dr. Apollinaire William, an agricultural landscape researcher, highlighted the dangers of chemical runoff. “When farmers overuse industrial fertilizers, these substances seep into nearby rivers and marshes, poisoning aquatic organisms and disrupting ecosystems,” he explained.

Environmental researcher Uwimana Marthe elaborated on the impact: “Rainfall washes excess fertilizers into the soil and carries them into water bodies. Once in stagnant waters, these chemicals harm aquatic species like fish, frogs, toads, and worms, which play vital ecological roles. For instance, frogs and toads feed on mosquito eggs, naturally controlling their population. Their decline has allowed mosquitoes to proliferate unchecked.” She also pointed out the risks to humans, noting that people who bathe in or consume contaminated water may also suffer health consequences.

The effects are already visible. Once home to thriving frog and toad populations, the Rugeramigozi marsh has seen a drastic decline in these amphibians. The result? A surge in malaria cases, as mosquitoes multiply without natural predators. The same pattern has emerged in Bugarama and Cyamura marshes in Rusizi District, where local health centers have reported a sharp rise in malaria infections. Data from the Rwanda Biomedical Center (RBC) shows that over 83,000 malaria cases were recorded in January alone, raising alarms about the long-term impact of agricultural pollution even though it is not the unique reason.

Marthe Uwimana emphasized that frogs and toads, as key indicators of environmental health, are particularly sensitive to chemical exposure. “The disappearance of frogs and toads is a clear warning sign of ecological imbalance. Without them, mosquito populations explode, leading to increased disease transmission,” she cautioned.

Beyond the rise in vector-borne diseases, experts also highlight the direct health risks posed by fertilizer-contaminated water. Kamana Eric, a public health specialist, explained how nitrates and phosphates from fertilizers seep into drinking water sources, making them unsafe for consumption and increasing the risk of waterborne diseases.

“This is not just a solely environmental issue; it’s also a public health crisis. Contaminated water doesn’t just affect those who drink it. It disrupts the entire food chain, from fish to livestock, and ultimately endangers human life,” warns, Dr. Ngarukiye Vedaste a public health expert.

The soil under double threat

Dr. Apolinaire William, an Agricultural Landscape Researcher, highlights that excessive reliance on chemical fertilizers without integrating organic alternatives is not only depleting essential soil nutrients but also exacerbating erosion. “Over time, these fertilizers weaken the soil structure, making it more vulnerable to erosion, especially in hilly regions,” he explains.

In the Virunga Mountains, the impact is already evident. According to Anastase Nduwayezu, a potato pathology researcher at the Rwanda Agriculture and Animal Resources Development Board (RAB), the overuse of pesticides and fertilizers has severely disrupted soil nutrient balances. “Soils in these areas are suffering from mineral deficiencies, which directly affect plant growth and overall crop yields”, he warns.

According to a study by the Rwanda Agriculture Board, improper fertilizer use reduces long-term soil fertility, resulting in declining crop yields over time.

“Farmers who rely heavily on chemical fertilizers without supplementing with organic matter are depleting their soil’s natural productivity”, warns Karinganire Eric, an agricultural economist. He calls for a balance between organic and inorganic fertilizers to maintain soil health and protect farmers’ livelihoods.

Beyond environmental and health risks, the misuse of fertilizers has economic consequences. Farmers, driven by short-term yield increases, often overspend on chemical inputs, leading to debt cycles.

Government acknowledges the crisis and takes action

Dr. Mark Cyubahiro Bagabe, Rwanda’s Minister of Agriculture, admitted that past one-size-fits-all fertilizer recommendations had led to inefficiencies in farming. “For years, fertilizers were applied without considering the unique needs of different soils and crops,” he stated at the official launch of the Rwanda Soil Information Service (RwaSIS) in November 2024. He emphasized that this new digital initiative aims to address critical challenges in agriculture, including the misuse of fertilizers and the underutilization of Rwanda’s diverse agro-ecological zones. He pointed out that previous blanket recommendations sometimes led to excessive application of nutrients like potassium, even in soils that didn’t need it; wasting resources and potentially harming soil health.

The Rwandan government has launched several initiatives to educate farmers on the proper use of industrial fertilizers, aiming to boost agricultural productivity while protecting the environment. Since 2014, Farmer Field Schools (FFS) have played a pivotal role in equipping Rwandan farmers with essential agricultural knowledge. These hands-on training programs have become a vital platform for sharing best farming practices, including the responsible use of inorganic fertilizers. Through FFS, farmers not only learn how to maximize yields but also how to do so sustainably, ensuring long-term soil health and environmental protection.

The Rwanda Soil Information Service, launched in 2020, provides farmers with site-specific fertilizer recommendations based on soil mapping. The Smart Nkunganire System, launched in January 2025, integrates digital tools to offer personalized advice on fertilizer application.

While these initiatives represent significant progress, challenges persist. Pamphile Kagiraneza, an expert in climate-friendly agriculture, emphasizes the need for greater awareness. “Organic fertilizers are not only better for the environment but also for human health,” he explains. He urges the government to tighten regulations and actively promote sustainable alternatives, ensuring that farmers have both the knowledge and incentives to adopt eco-friendly practices.

This highlights the government’s recognition of the risks posed by improper industrial fertilizer use. But where do the gaps remain?

More farmers unaware of the dangers

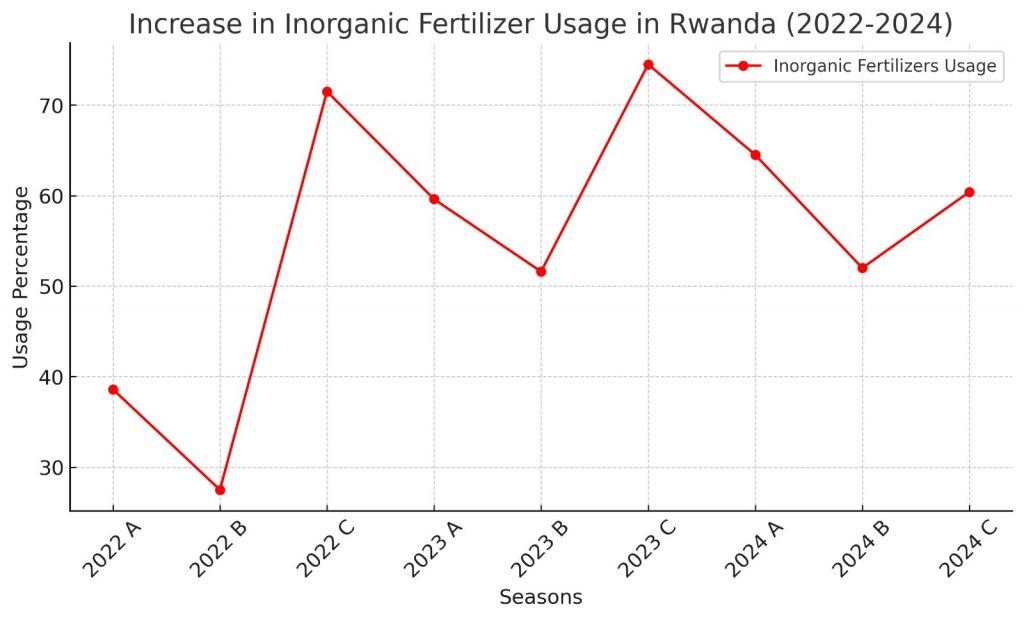

Despite its risks when it is misused, industrial fertilizer use continues to rise in Rwanda. A report of Rwanda National Institute of Statistics reveals that between 2022 and 2024, the application of inorganic fertilizers increased significantly. While Rwanda’s total land area is 2.377 million hectares, over 56 percent is dedicated to agriculture, making fertilizer management crucial.

In Rwanda, 85% of rural households farm on less than one hectare of land. Many of these plots suffer from poor soil quality, and farmers often apply fertilizers based on personal experience rather than scientific guidance, notes agricultural specialist Rukemampunzi Sam.

Marc Cyezimana, a resident of Cyeza sector in Muhanga district, has been growing cassava for over ten years, and he says it has improved his livelihood. Since he does not own enough land, he borrows plots to cultivate.

Regarding the use of fertilizers, he mentions that he is familiar with them because he has been using them for a long time. However, he adds, “I never received formal training on this since I am not part of any agricultural cooperative. I simply learned by observing others and doing the same.”

When asked if he uses organic fertilizer to preserve soil quality, he responds, “Organic fertilizer is good because it stays in the soil longer. However, I rarely use it because it takes time to produce results. Since the land I farm is not mine, I prefer chemical fertilizers, which give quick yields, allowing me to return the land to its owners with a good harvest.”

Cyezimana is not the only one who lacks proper knowledge of how to use chemical fertilizers. This issue is shared by many small-scale farmers cultivating hillside plots in the districts of Nyabihu, Burera, Rusizi, and Nyaruguru, where we visited and discussed their agricultural knowledge.

Although Rwanda has trained agronomists specializing in agriculture, when asked whether they receive support from them, some farmers respond, “We occasionally hear about them or see them working with farmers in cooperatives or large-scale producers. But as for us, small-scale farmers, they don’t pay us any attention at all.”

“Seventy percent of Rwandans are engaged in agriculture, yet most rely on traditional knowledge rather than modern techniques,” says agricultural specialist Kamanayo Eric. He notes that even small-scale farmers who have easy access to organic fertilizers often sell them to larger farms that practice sustainable agriculture. “As a result”, he adds, “these farmers become dependent on chemical fertilizers, despite the long-term benefits of organic alternatives.”

However, the leaders of the COCAR cooperative, which represents farmers in the Rugeramigozi marshland in Shyogwe sector, Muhanga district, as well as those of the KOIMUNYA cooperative in Mashyuza cell, Nyakabuye sector, Rusizi district, emphasize their efforts in educating farmers on the proper use of chemical fertilizers.

“Whenever we notice improper application, we take the time to educate farmers or, in some cases, apply the fertilizer ourselves as cooperative leaders,” they explain. “Additionally, we work closely with agronomists who provide hands-on support to the farmers, ensuring best agricultural practices are followed.”

Yet, many farmers remain unaware of the dangers. Cooperative-based training programs exist, but most smallholder farmers do not belong to cooperatives, leaving them without access to vital information on responsible fertilizer use.

Towards a sustainable agricultural future

The case of Mukamwiza Thérèse and her neighbors is a warning sign. If Rwanda does not act swiftly to regulate chemical fertilizer use, the health of both people and the environment will continue to deteriorate. Strict enforcement of sustainable farming practices, combined with widespread education, is necessary to prevent further ecological damage.

A shift towards responsible fertilizer use is not just an environmental necessity. It is a matter of public health and economic stability. The government needs to ensure that all farmers, whether they belong to cooperatives or not, have access to the right training on sustainable fertilizer use.

Eric Karinganire, an agricultural economist, stresses the need for a more proactive approach in educating farmers on proper fertilizer use. “It is not enough for the government to wait for occasional projects to train farmers, especially since these initiatives often reach only a select few who are already financially capable,” he argues.

Instead, he calls for a continuous, inclusive education system that benefits all farmers, regardless of size or affiliation. “There should be a permanent framework to educate both small-scale and large-scale farmers, whether they are in cooperatives or working independently,” he insists.

To achieve this, apart from keeping close to farmers on field, Karinganire suggests leveraging multiple communication channels: “Regular discussions on radio, educational messages on social media and mobile phones, awareness sessions in community meetings, these are all powerful tools. Even fertilizer vendors should be trained to advise farmers on proper usage, just as pharmacists instruct patients on medication use.”

Strengthening soil health monitoring through frequent soil testing will also be essential in reducing unnecessary chemical applications. Additionally, promoting organic farming and providing incentives for compost, manure, and bio-fertilizers will help reduce the overreliance on synthetic fertilizers.

Investing in research and innovation should be a priority to explore sustainable farming techniques that can support long-term agricultural productivity without compromising the environment. Without immediate and strategic intervention, the degradation of Rwanda’s agricultural land will continue, affecting food security and public health.

“Additionally, more farmers must be trained to produce and use compost, which not only enriches the soil but also offers a cost-effective solution compared to synthetic fertilizers”, suggests, Karinganire Eric.

Learning from global practices

Other countries have tackled similar issues by adopting integrated nutrient management, which combines organic fertilizers, composting, and precision agriculture. Rwanda could benefit from such strategies by encouraging the use of locally available organic fertilizers, such as manure and compost, instead of over-relying on imported synthetic fertilizers.

In India, for example, the government has introduced subsidies for organic fertilizers and training programs to educate farmers about their benefits. In Europe, strict regulations control the amount of chemical fertilizers allowed per hectare to prevent environmental damage. Experts like Dr. Ngarukiye Védaste argue that Rwanda should consider similar policies to ensure sustainable agricultural growth.

“As Rwanda navigates the challenges of modern agriculture, the path forward lies in a balanced approach that prioritizes education, sustainable farming practices, and responsible fertilizer use. By strengthening farmer training programs, enforcing stricter regulations on chemical inputs, and investing in organic alternatives, the country can safeguard its environment and public health. The fate of Rwanda’s soils, water bodies, and communities depends on the choices made today”, suggested Uwimana Marthe, an environmental researcher.

By Telesphore KABERUKA